The Emigration of Filmmakers Under National-Socialism

The expulsion of filmmakers from National-Socialist Germany has to be considered in light of the Nazis persecution of nonconformists, the criminal war they initiated, and their murder of over six million European Jews and other minorities persecuted on racial or political grounds. For the overwhelming majority of emigrants the escape from their own country was an experience undertaken under considerable economic duress and personal suffering; and yet it was the only way possible for them to save their lives.

Exclusion and Defamation

Adolf Hitler's inauguration as Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933 marked the end of the first German democracy; immediately upon taking power the National-Socialists began pushing the institution of their abominable ideology in all areas of society. The film industry in particular, as Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels emphasized in his Hotel Kaiserhof speech, given March 28, 1933 in Berlin before a congress of the Umbrella Organization of German Filmmakers, a.k.a. "Dacho". What Goebbels called the "spiritual crisis" of German film provided a pretext, one consistent with National-Socialist racism and anti-Semitism, for discriminating against and systematically debarring all Jewish filmmakers from the industry. The day after Goebbels' speech, on March 29, 1933, Ufa's board of directors passed the following resolution:

"With regard to the question raised by Germany's national revolution concerning Ufa's further engagement of Jewish workers and staff, the board of directors has resolved to revoke as far as possible its contracts with Jewish personnel." Ufa then promptly laid off several of its most prominent artists, including producer Erich Pommer and director Erik Charell. Together the two were responsible for "Der Kongreß tanzt" (The Congress Dances), Germany's most successful film in 1931. Their fate exemplifies the internal persecution combined with public denunciation Jews in the film community faced: producers, directors, actors, screenwriters, composers, architects, cinematographers, technicians alike. Even long-standing industry publications such as "Film-Kurier" fired now-undesirable writers and began publishing articles lambasting "studio Jews".

This political and juridical repression grew even more with the founding of the Reich Chamber of Film in July 1933. Membership, which was basically limited to "Aryans", became a prerequisite for any and all employment in the German film industry; a few artists thus excluded were granted a limited-term special permit, including the successful comedy director Reinhold Schünzel. January 1935 saw the final exclusion of "Non-Aryans" from the Reich Chamber of Film. By that point, the majority of affected filmmakers had already left Nazi Germany.

A New Start in Dire Straits

The forced exile meant making a new, uncertain start in a foreign country. The individual's specific profession and the legal and economic conditions of the film industry in the country of exile determined what the emigrant ended up doing. Actors and screenwriters in particular were confronted with linguistic barriers that made continuing their career problematic or simply impossible.

So for example in France, the most important country in discussing emigration in Europe, an actor with a German accent was unacceptable, which is why it was directors and producers — albeit often with great difficulty — who found work there. Directors successfully employed in France at times included Max Ophüls, Robert Siodmak, Fedor Ozep, and Richard Oswald. Even Erich Pommer worked as a producer in Paris before moving on to Hollywood. In Great Britain, on the other hand, actors like Elisabeth Bergner, Adolf Wohlbrück, and Fritz Kortner did find engagements and were able to re-establish their careers in large measure thanks to producers who had also emigrated. Many German actors tried to find work in Austria. But the state-run film industry there followed Germany's anti-Semitic policies and likewise barred Jewish filmmakers from employment; thus, star comedians like Szöke Szakall or Felix Bressart were able to appear exclusively in independent productions. Before Austria's "Anschluss" with Nazi Germany in March 1938 put an end to this possibility, too, the Deutsche Universal film company, based in Vienna and Budapest, was known for making successful German-language films with Jewish artists. Especially popular were the comedies made by director Hermann Kosterlitz and writer Felix Joachimson together with their star Franziska Gaal. In 1936, the team left for the United States: given the increasingly dire situation in Europe, more and more people who had initially decided to remain were fleeing.

Vanishing Point Hollywood

When the Nazis seized power, many persecuted filmmakers straightaway attempted to establish a new life in Hollywood. In the 1920s, the world's largest film industry had been a magnet for numerous prominent artists from Germany, and now celebrities like Fritz Lang followed. Alongside Jewish emigrants like Peter Lorre, who made a name for himself in the States as a character actor, and Billy Wilder, whose international career as a writer/director only really began in the U.S., came political exiles like Bertolt Brecht and the composer Hanns Eisler.

But for every success story like Wilder there were thousands of émigrés who were able to survive in the American studio system only by the skin of their teeth or thanks to the support and solidarity of the exile community. Especially with regard to the technical vocations, the unions were anxious to protect the interests of their American members, which is why cameramen like Curt Courant and Eugen Schüfftan were rarely officially allowed to work on productions.

Furthermore, the U.S. government was making it difficult to immigrate because of the rising numbers of refugees. With Germany's invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939 and start of World War II in Europe, the United States became for most of the Nazis' victims the last safe haven. Many émigré filmmakers — including Kurt Gerron, Otto Wallburg, and Paul Morgan — were unable to escape. They were murdered in German concentration camps.

Solidarity With the Persecuted

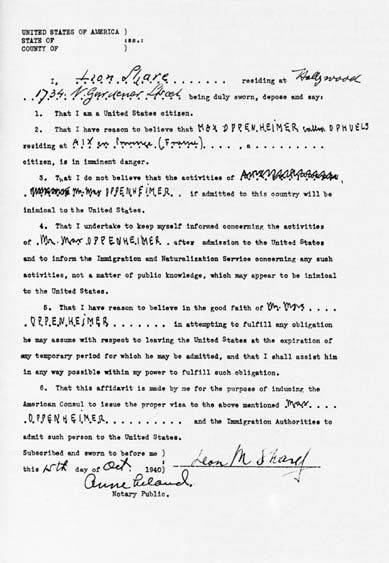

The U.S. government attempted to control the surge of refugees by making conditions for immigration more restrictive. Presentation of an "affidavit" — a guarantee by an American citizen to financially support the immigrant if necessary — thus became necessary for admission into the country. In this situation, in which entry was literally a matter of life or death, the producer and Hollywood agent Paul Kohner stands out for his commitment and self-sacrifice in rescuing countless filmmakers in distress. He arranged for not only the essential affidavits but also contracts with major studios in Hollywood for writers who otherwise had no chance at all, including Alfred Döblin. In addition, he was a driving force in the European Film Fund, which supported the majority of indigent émigrés.

The war, however, also created a greater demand for German-speaking actors in Hollywood. With the U.S.'s entry into the war in 1941, the production of "anti-Nazi films" increased, and émigré actors were in favor — frequently finding themselves cast as the fanatical Nazi war criminal. Many actors had only a limited spectrum of roles available to them, which gave rise in Hollywood to the disparaging moniker "accent clown". The fate of these émigrés has been elucidated in part by film historian Jan-Christopher Horak, who has for years researched and published on exile filmmakers.

The Resistance and Anti-Fascism

Despite having their own vocational difficulties to deal with, the overwhelming majority of émigrés in Hollywood actively supported the U.S.'s fight against the Nazi regime. Whether by participating in films and radio broadcasts that appealed to the German people to resist Hitler, by working for immigrant aid and the support of troops, and even — if they had gotten American citizenship — by actively serving in the U.S. military. One person who stands out for her special commitment is Marlene Dietrich, who began her Hollywood career in the early 1930s and remained in the U.S. despite lucrative offers from Nazi Germany to return. She was among those artists of German ancestry who saw themselves morally and ethically obliged to resist the National-Socialist state even if they were not directly victims of its policies. Dietrich's express support for the fight against fascism and the fact that during the war she was active in numerous charities made her sincerely appreciated far beyond Hollywood.

Return to the Unknown

Filmmuseum Berlin - Marlene Dietrich Collection

The Allied victory over Germany gave the survivors of the Nazi terror the possibility of returning; but for most of the émigrés return was no longer an option. Knowledge about the Holocaust and the loss of family members and friends who had been murdered under the National-Socialists made going back unthinkable. Besides, many of the émigré filmmakers had established a new life outside Germany. Re-émigrés from the film industry thus often included actors who had not succeeded abroad due to the language barrier and now hoped for new career possibilities. For many, the return to their home country was fraught with the painful realization that the majority of the German populace had no interest in honestly admitting and working through their guilt.

Two exceptional films from the post-war years were Fritz Kortner's "Der Ruf" and Peter Lorre's "Der Verlorene". These films were the work of artists who had been forced into exile and who were attempting to come to terms with the recent past. Yet they were denied public recognition.