The Emergence of German Sound Film

Sound and image already went hand in hand early on in the history of film. Even in the silent-film era, the presentation of film was thoroughly bound up with sound. Starting from film's very first years, in the mid-1890s, those early reels, which were then still just a component of a live stage show, were accompanied by a varieté orchestra. Well into the late 1920s, sound remained a constant companion of film—whether by means of piano, chamber ensemble, or the movie organs that were developed in the 1910s. And yet the breakthrough of sound film - the synchronized linking of an image with its corresponding sound - was not achieved until a good 30 years after the invention of film.

Singing Pictures: “The Jazz Singer” and Vitaphone

The revolution in the relationship between sound and image, the triumph of the sound film, began at the end of the 1920s. The first highpoint of this radical change may be dated October 6, 1927. On this day, the premiere of the first "talkie" was celebrated in New York City with the opening of the Warner Bros. film, "The Jazz Singer". It was in this film that the varieté star Al Jolson uttered the famous first words of synchronous speech: "You ain't heard nothin' yet!" The new synchronization of sound and image was made possible by the Vitaphone system developed by Warner Bros. and Western Electric. In this sound-on-disc process, the film projector was connected to a recording disk that was scraped by a needle. But the celebrated sound-on-disc system remained in use for only a few years - in the 1928 film "The Singing Fool", for instance - before it was replaced by another, more successful principle: the sound-on-film process, which enabled the world-wide spread of sound film, and which had already been put to use in Germany ten years previously.

First (Failed) Attempts: The Sound-on-Film Process and Tri-Ergon

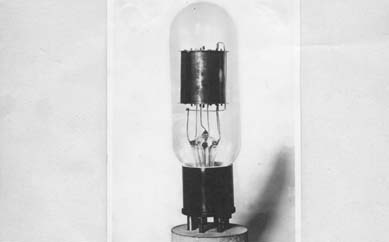

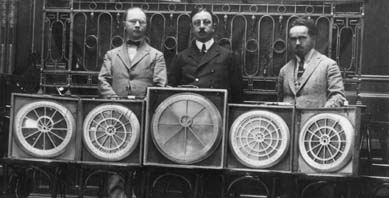

In 1918, the three German technicians Joseph Engl, Joseph Masolle and Hans Vogt began working on the development of a sound-on-film process, which they called Tri-Ergon (the work of three). By 1921/22, the attempt to link the running film strip with a soundtrack traced along its edge by a beam of light had begun to show first signs of success. However, the investors still held back. The patents were turned over to Tri-Ergon AG (founded in Zurich by Swiss financiers) in 1923, before the German film company Ufa resolved to form a partnership in 1925. The sound-film pioneer Guido Bagier was named artistic director of the Tri-Ergon Department of Ufa - which at last produced its first short sound film, "Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern" (The Little Match Girl), in a film studio in Berlin-Weißensee that was built especially for the occasion. But the premier of the barely 20-minute-long film on December 20, 1925 ended in catastrophe: during the viewing in Berlin's Mozartsaal, the sound cut out, and the invited guests responded to the malfunction with ridicule and protest. According to the legend that arose soon after, foreign saboteurs had "finished off German sound film". In any case, after this set-back, Ufa pulled out of the sound-on-film project. It was only years later, after the success of Vitaphone's technically impractical sound-on-disc process, that the sound-on-film technique based on Tri-Ergon, among others, finally gained acceptance. In Germany and Europe, it would not be Ufa, but Tobis that would make the decisive contribution to that end.

Syndicate for Sound Film: Tobis

Tobis was founded in Berlin on August 30, 1928 as the Ton-Bild-Syndikat AG (Sound-Image Syndicate). It emerged out of Tri-Ergon Musik AG - at the insistence of the Deutscher Tonfilm AG (German Sound Film), which was striving for the standardization of European sound film technology. The most prominent European patent-holders and electrical products firms were to be encouraged to work together in order to stand up to the competition of American sound films and technologies. Sound film, or more precisely, the "talkie", was unquestionably the film to come. Therefore, it was imperative to secure the markets for the new film and to make practical use of the sound-film patents consolidated under Tobis. In contrast to Ufa, then, Tobis - which soon found itself with a majority stake in the Dutch company Küchenmeister - was geared towards international cooperation from its inception. And a further decisive connection was made in 1929. Tobis and its original competitor, Klangfilm GmbH entered into a cartel agreement that divided the market between the two firms. Meanwhile, Ufa and Klangfilm planned in a separate contract to develop their own sound film production. Thus, from then on, Tobis stood in direct competition with the giant Ufa as a producer of film.

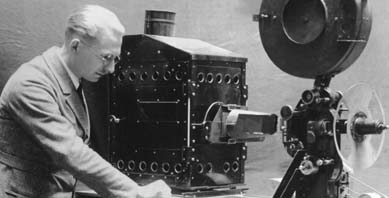

But it was not only for this reason that 1929 became an important year in the history of both Tobis and German sound film. After the Tri-Ergon film "Ein Tag Film" (One Day of Film), the film "Ich küsse ihre Hand, Madame" (I Kiss Your Hand, Madame) marked the premiere of the Tobis system on January 16, 1929 with a series of songs sung by Richard Tauber. Barely two months later came the premiere of Walther Ruttmann's Tobis film "Melodie der Welt" (Melody of the World), which, at some 40 minutes, was the longest German sound film at the time. On September 30, the premiere of Carmine Gallone's Tobis production, "Das Land ohne Frauen" (The Land Without Women) - almost two hours long - was greeted by the press as "the first feature-length German sound film".Thus it came about that, on the one hand, Tobis functioned as a film production company. On the other hand, together with Klangfilm, it profited doubly from the rise of sound film by offering its technology to other production companies such as Ufa. The recording process was marketed under the name "System Tobis-Klangfilm"; the play-back equipment was offered under the name "System Klangfilm-Tobis". In this manner, the Tobis-Klangfilm cartel assured itself the best chances of survival during the turbulent inception of sound film - which the critic Rudolf Arnheim described in 1929 as "sound-film confusion".

The Future is Secured: the "Sound Film Accord"

The year 1930 brought clarity for the national and international development of sound film. Successes and decisions set the course for the future. Films such as "Die singende Stadt" (The Singing City) and "Der Schuß im Tonfilmatelier" (The Shot in the Talker Studio), praised by Erich Kästner for having "subjects appropriate to sound film" skillfully made use of the new possibilities. The same year saw the emergence of sound film classics such as "Der blaue Engel" (The Blue Angel) and "Die Drei von der Tankstelle" (Three Good Friends), which became the most successful film of the season. In April 1930, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Berlin reported: "By now, sound film has become firmly established."

But success brought new international disputes. Struggles broke out world-wide over sound-film patents that controlled access to disparate portions of the world market. The quarrels were to be settled at an international conference in Paris.This was accomplished with the accord of July 22, 1930, which became known as the "Paris Sound-Film Accord". In this accord, the Tobis-Klangfilm group and representatives of the US sound-film industry agreed to split the areas of interest: The German group was allotted the markets of Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, as well as Scandinavia and the Baltic states; the US firms were given the American market. Both sides were allowed to compete in the remaining countries. Only then did it become possible to lay the groundwork upon which, according to Guido Bagier, "the future of film" would be developed worldwide.